Antecedentes

Época colonial y republicana

En las primeras décadas de la época colonial, el valle de Majes, uno de los más grandes y ricos de todo el sur del Perú, fue dividido entre los terratenientes españoles. La producción de vid para vinos y piscos, así como la producción de aguardiente, fueron el principal comercio emblemático de la zona. Toro Muerto formó parte de una de las mayores haciendas del valle y sirvió durante siglos como una fuente gratuita de material de construcción, conocida - incluso - entre los locales como 'La Cantera'. Sus piedras se utilizaron para construir tanto las casas y edificios de granjas o bodegas, como la capilla de la orden jesuita (terminada en 1722), ahora conocida como El Santuario de Huarango. Los últimos propietarios de la hacienda de Toro Grande antes de la reforma agraria - la familia Revilla - utilizaron bloques de toba volcánica provenientes del sitio arqueológico para construir una destilería (en los años 20 y 40).

¿Cuándo y cómo se descubrió Toro Muerto?

El interés y las primeras investigaciones serias sobre el arte rupestre en el sur del Perú - y especialmente en la región de Arequipa - pueden ser relacionadas con el nombre del sacerdote, historiador y arqueólogo aficionado Leonidas Bernedo Málaga (1891-1977) que estuvo especialmente activo entre los años 30 y 40 siendo vicario y párroco en la ciudad de Chuquibamba. Es muy posible que fuera él el primero en enterarse de la existencia de un majestuoso sitio en el valle de Majes, aunque probablemente nunca llegó a conocerlo personalmente. Por consiguiente, esta información no obtuvo entonces mucha publicidad.

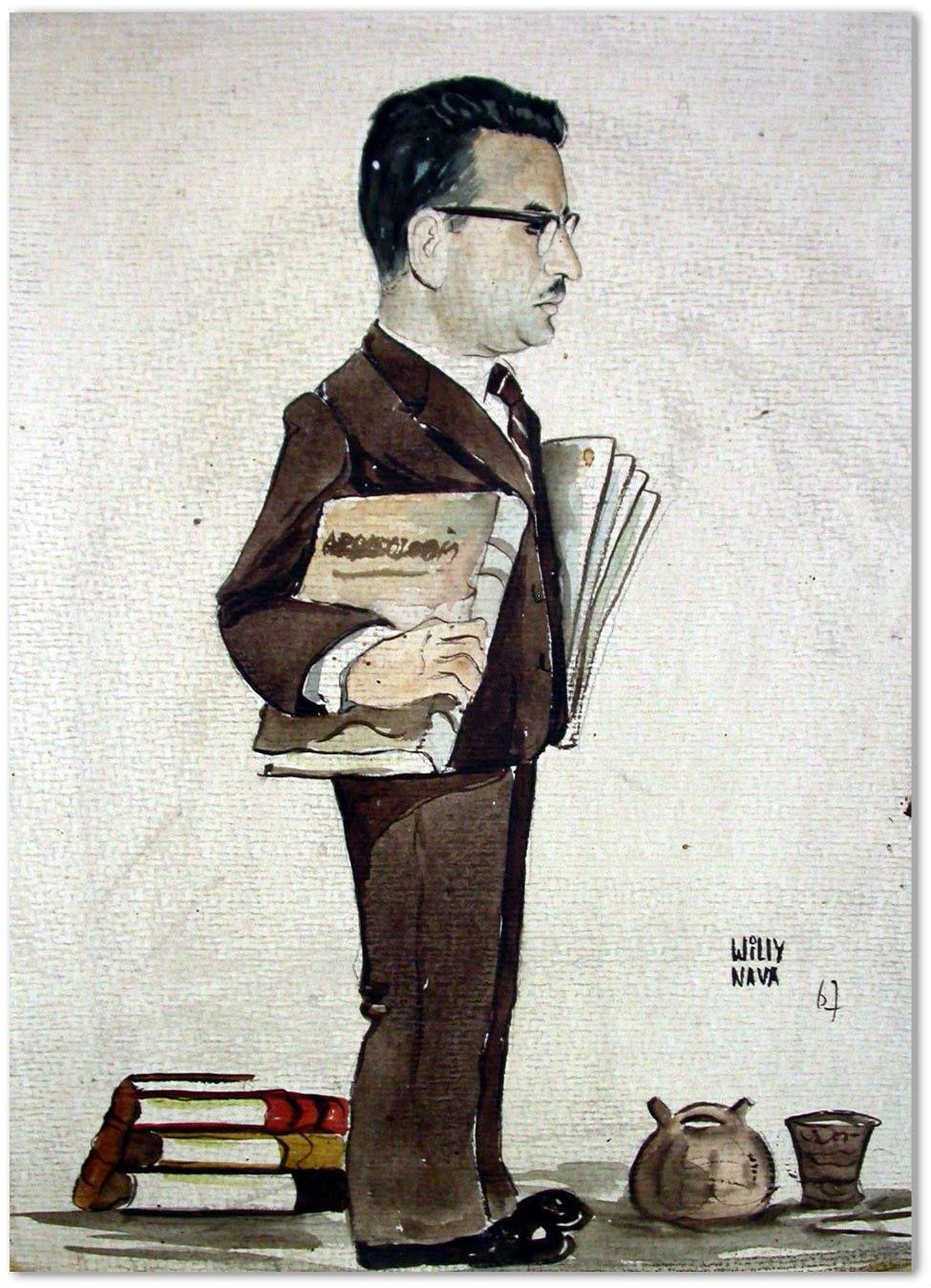

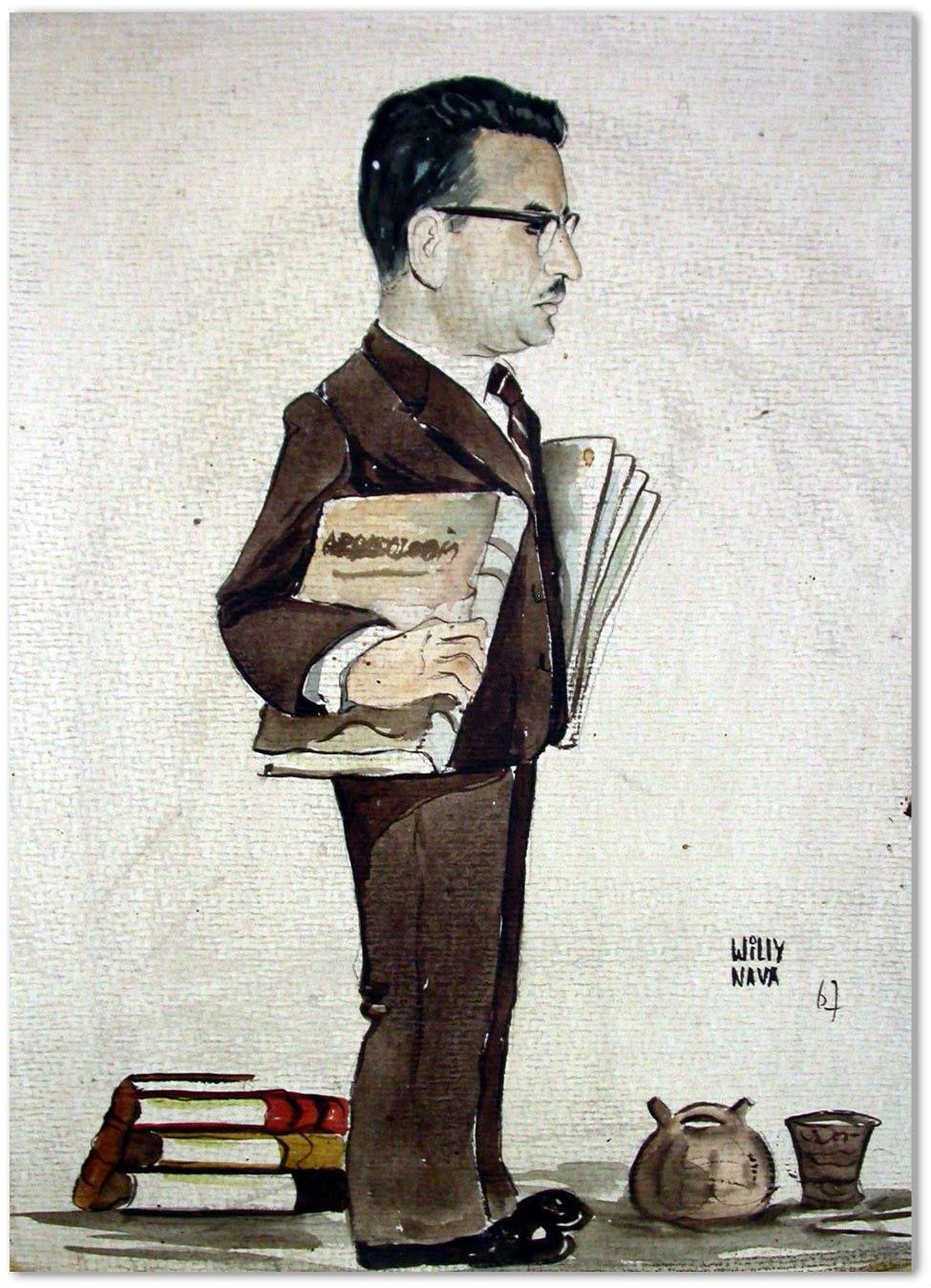

Leonidas Bernedo Málaga y su más conocido libro La cultura Puquina (1949)

Un dato interesante es que mucho antes de este descubrimiento, el sitio estuvo también al alcance del explorador americano Hiram Bingham - el 'descubridor para la ciencia' de Machu Picchu - quien en 1911 organizó una expedición que terminó con la llegada al Nevado Coropuna. Del Valle de Majes se posee una foto de este explorador, parado cerca de un gran bloque de toba volcánica decorado con petroglifos. Sin embargo, no se trata de una foto de Toro Muerto, sino del sitio vecino llamado Pitis, Alto de Pitis o La Mesana que se encuentra frente a Toro Muerto, en la ribera contraria del río.

Hiram Bingham en Alto de Pitis - La Mesana (Valle de Majes, 1911)

Toro Muerto es - finalmente - descubierto para la ciencia a principios de la década del 50 (muy probablemente en agosto del 1953) por un pariente lejano del monseñor Bernedo Málaga: el joven investigador de la Universidad Nacional de San Agustín en Arequipa, Eloy Linares Málaga (1926-2011) y su compañero de viaje al Valle de Majes, el distinguido arqueólogo alemán Hans Dietrich Disselhoff (1899-1975). Este último anuncia el hecho por la primera vez en una conferencia organizada en Alemania en 1954, luego lo publica en la revista Baessler-Archiv en 1955 y después en sus libros de divulgación.

Hans Dietrich Disselhoff y su libro Gott muss Peruaner sein (1965)

Disselhoff y Linares colaboran por mucho tiempo. Sin embargo, a finales de los años 60 o principios de los 70, sus caminos se separan. A partir de este momento Linares Málaga se proclama como el único y oficial 'descubridor de Toro Muerto para la ciencia' y da inicio a la ya conocida historia acerca del descubrimiento (versión, dicho sea de paso, muy similar a la que acompaña al descubrimiento de Machu Picchu por Bingham). La fecha oficial del descubrimiento invariablemente citada por Eloy Linares Málaga en sus publicaciones es de 5 de agosto de 1951.

Eloy Linares Málaga (1986) y uno de sus articulos sobre Toro Muerto

Las décadas de los 50 y 60

Campamento de la Misión Arqueológica Francesa en Toro Muerto - 1965 (Musée du quai Branly No. Inv. PF0115696)

Encuentro de arqueólogos: Henry Reichlen, Hans D. Disselhoff, Paulet Barret-Reichlen, Eloy Linares Málaga

(Musée du quai Branly No. Inv. PF0106952_02)

Eloy Linares como empleado y, sucesivamente, director del Museo de la Universidad Nacional de San Agustín - hoy conocido como Museo Arqueológico 'José María Morante' - realizaba los trabajos de investigación en Toro Muerto principalmente en la década del 50 (con sus estudiantes de la universidad) y en 1965 (junto a Disselhoff). Durante estas temporadas de trabajo de campo se tomaron las primeras fotos documentales de las rocas grabadas, calcos y dibujos a mano alzada de algunos petroglifos, así como el primer plano del sitio (parte sur). Se efectuó también el primer intento de numerar y catalogar las rocas; desgraciadamente, en varios casos los rótulos colocados por el arqueólogo arequipeño se pintaron con óleo y en dimensiones muy grandes. Efectos de sus trabajos Linares presentó en su tesis de doctorado (sustentada en 1974), así como también en sus numerosos libros y artículos científicos y de difusión.

Hasta su muerte en 2011, Linares - quien dedicó toda su vida profesional a la arqueología de la región - luchaba por la promoción científica y turística de Toro Muerto. Publicaba, participaba en conferencias y simposios, y daba charlas al público general.

Él otorgaba a Toro Muerto el título de 'Machu Picchu de Arequipa' y estaba sumamente preocupado tanto por su destrucción continua, como por la falta de protección de parte de las autoridades locales, regionales y nacionales, y también por el poco interés por parte de los investigadores. Incluso a edad avanzada, siempre estuvo dispuesto de acompañar a los colegas 'rupestrólogos' durante sus visitas al sitio.

Entre los investigadores que realizaron estudios en la época pionera de los 60, hay que mencionar también al director de la Misión Francesa: el arqueólogo Henry Reichlen y su esposa Paule Barret-Reichlen; quienes en 1965 - disponiendo de autorización emitida por la Casa de la Cultura del Perú - ejecutaron el primer intento de documentación fotográfica sistemática para Toro Muerto. Desgraciadamente, por razones personales, este proyecto pronto fue descontinuado habiendo registrado únicamente 190 rocas en la parte sur del sitio, y recolectado una serie de materiales culturales de la superficie. En la actualidad, el material fotográfico de los Reichlen se encuentra custodiado por el Musée du quai Branly en París, y una parte del material recolectado (herramientas de piedra, lajas pintadas, fragmentos de cerámica) se halla almacenado en el Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú en Lima.

Las décadas de los 70 y 80

Antonio Núñez Jiménez

y Eloy Linares Málaga

Al final de la década de los 70, se realiza la primera documentación fotográfica extensa de Toro Muerto elaborada por uno de los más conocidos investigadores del arte rupestre de esta época: el geógrafo, espeleólogo, político y diplomático cubano Antonio Núñez Jiménez (en los años 1972-1978 - embajador de su país en el Perú). En base a su material gráfico - ya en Cuba - sus colaboradores preparan los dibujos de los petroglifos. Todo el material gráfico preservado de este proyecto se encuentra actualmente resguardado en la Fundación Antonio Núñez Jiménez de la Naturaleza y el Hombre, en Cuba.

Antonio Núñez Jiménez entrega su libro a Gabriel García Márquez

En 1985 Núñez - ya como el Viceministro de Cultura - organiza en la ciudad de la Habana el Primer Simposium Mundial de Arte Rupestre auspiciado por la UNESCO. Eloy Linares Málaga, uno de sus invitados principales, postula allí la proclamación de Toro Muerto como 'repositorio del arte rupestre más grande del mundo' y su inscripción a la lista del Patrimonio Mundial de la UNESCO. En el mismo año el científico cubano publica también su libro de dos tomos Petroglifos del Perú: Panorama Mundial del Arte Rupestre con casi tres mil dibujos y fotos de los grabados del país andino. La segunda edición del libro se publica un año después en cuatro tomos; gran parte del tomo IV es dedicado principalmente a Toro Muerto. En 1986 este mismo material se publica también por separado en El libro de piedra de Toro Muerto.

El libro de Núñez Jiménez constituyó, por varias décadas, la obra referencial para todos aquellos que se ocupaban del arte rupestre del Perú. Los dibujos allí presentados servían para ilustrar artículos y libros de otros autores. Desgraciadamente, como fueron realizados en base a fotografías (muchas veces oblicuas), varios presentaban grandes distorsiones. Lastimosamente los dibujos fueron realizados por colaboradores que probablemente nunca vieron personalmente los petroglifos de Toro Muerto (y otros sitios descritos por el autor), ya que no son muy exactos y a veces erróneos.

En 2004, en honor al gran investigador cubano y por el estudio del arte rupestre de Toro Muerto (y del Perú) en frente de la Facultad de Comunicaciones de la UNSA se instaló una placa conmemorativa dedicada a él. Un poco después se inauguró un pequeño parque con su nombre donde encontraron lugar unas cuantas rocas con petroglifos transportadas por Linares Málaga a la ciudad Arequipa todavía en los años 70.

_edited.jpg)

_edited.jpg)

La década de los 90 y primeros años del siglo XXI

Pasaron nuevamente otros 20 años de silencio en los estudios científicos o propuestas metodológicas, hasta que en 1998 se realizó un reconocimiento con levantamiento perimétrico por parte de la sede regional del Instituto Nacional de Cultura en Arequipa (INC-A). Se marcaron entonces los límites del sitio (50 km2) y se creó el primer plano topográfico detallado del complejo. Así mismo, se colocaron las nuevas codificaciones (números de inventario) en el cuerpo de las rocas. Para tal proyecto se utilizaron métodos de levantamiento topográfico con los instrumentos disponibles en aquel momento (teodolito) y se logró inventariar una gran parte del sitio con unas dos mil rocas aproximadamente.

A principios de este siglo, se desarrollaron otros tipos de intervenciones en Toro Muerto, enfocados principalmente en el registro adecuado de las rocas y sus paneles tallados. Un ejemplo es la de Muriel Pozzi-Escot que, en el 2000 y en base al plano del INC-A, realizó la documentación de fichas y fotografías de 1151 bloques. Su método consistió en la sectorización del sitio y centró su trabajo en el Sector A6, ubicado en la parte central del complejo y en un área de 1000 x 500 metros designada arbitrariamente por ella.

Plano general del sitio (Pozzi-Escott 2009: 358, Fig. 16)

Díaz Rodríguez & Daria Rosińska 2008: 84, Fig. 1.

Posteriormente, Daria Rosińska de la Universidad de Wrocław (Polonia) junto a Luis Héctor Rodríguez Díaz (2008, 2016), llevaron a cabo una prospección arqueológica en el perímetro del sitio y en la parte del valle. Sus trabajos se enfocaron principalmente en las características del paisaje y en algunos elementos culturales: cementerios, caminos, lugares de descanso y huellas de canales de riego. Adicionalmente, es necesario resaltar los trabajos realizados por un investigador holandés aficionado a los estudios rupestres, Maarten van Hoek (2003, 2005a, 2006, 2013a, 2018) que se centraron en la interpretación de algunos motivos de la iconografía de Toro Muerto, la cronología de los petroglifos y de algunos aspectos de su ejecución.

Sectores de trabajo y efectos de registro de los proyectos anteriores

La era de la tecnología digital

El registro de arte rupestre siempre estuvo acompañado de aparatos fotográficos y equipos de medición topográfica. Hasta los comienzos de nuestro siglo en arqueología se usaron cámaras clásicas (análogas) y teodolitos. Hay que tener en cuenta que la documentación detallada de un sitio tan extenso como Toro Muerto y de todos sus petroglifos era prácticamente imposible en aquel momento, aunque sólo fuera por los gastos de tal operación (rollos de películas necesarias para miles de fotos) y los problemas subsiguientes con el inventario y el procesamiento del material adquirido. La llegada del GPS, las cámaras fotográficas digitales, los RPA (drones) y el potente software para trabajos geodésicos revolucionó drásticamente la documentación arqueológica, facilitando, simplificando y acelerando todo el proceso. Esta evolución tecnológica ha visto su principal despegue en los últimos 20 años.

Trabajos de campo (2015-2016) y algunos efectos del Proyecto Arqueológico Toro Muerto

Entre el 2015 y 2016 se realizan tres temporadas de campo del Proyecto Toro Muerto (PTM) liderado por Karolina Juszczyk (Instituto de Arqueología, Universidad de Varsovia, Polonia) y Abraham Imbertis Herrera (Arquomática SAC, Perú). Durante ellas se registran y documentan aproximadamente unos 1650 bloques de piedra en un área de 3,80 km2. Así mismo se efectúa el primer ortofotomapa de la partes sur y central del sitio, algunos modelos 3D de las rocas grabadas y varios calcos de los petroglifos. Resultados de PTM se publican en la página web de dicho proyecto (www.toro-muerto.com).